What it means to be Fighter Fit

Elite athletes have long paid particular attention to strength and conditioning to ensure peak physical performance.

The Australian Institute of Sport defines strength and conditioning as « the provision of medical and physical services to develop and maintain speed, agility, endurance, strength, stability, flexibility, injury prevention, and management and rehabilitation for the purposes of enhanced athletic performance during competition. »

The rapid adoption of science-based strength and conditioning for elite athletes since the 1960s with the development of individual programs to cater to specific strengths and weaknesses has improved athlete movement and technique and has improved physical conditioning.

As a result, for non-contact sports in particular, the incidence of career-ending injuries has dropped in recent decades. And even without the insidious use of illegal performance-enhancing doping and improvements in equipment technology, records in almost every sport have continued to fall. Athletes continue to run faster and further for longer, balls are being thrown or hit harder and further, and heavier weights are being lifted.

Not surprisingly then, militaries around the world have started to study and adapt strength and conditioning principles, in particular for special forces soldiers and sailors, air force combat controllers and fast jet aircrew.

The results have been so encouraging that a strength and conditioning program is now being rolled out across Air Combat Group (ACG).

The Royal Australian Air Force is an early-adopter in implementing a strength and conditioning regime across its fast jet aircrews, starting in 2016 with a trial at Williamtown-based 76 Squadron where the RAAF’s future fighter aircrew undergo the Introductory Fighter Course (IFC). The results have been so encouraging that a strength and conditioning program is now being rolled out across Air Combat Group (ACG).

Changing a culture

Dubbed Fighter Fit, the program has a three-pronged focus – a conditioning phase, a maintenance phase, and if necessary, rehabilitation.

It is not uncommon for RAAF fast-jet aircrew to sustain neck injuries, particularly performing basic fighter manoeuvres (BFM), which can lead to issues with medical approvals, which can see aircrew re-assigned to other aircraft types or retiring from flying altogether.

« It’s been a perennial problem for fighter aircrew », noted Wing Commander Carlos Almenara, executive officer of 78 Wing (which oversees 76 and 79SQNs, which operate the Hawk lead-in fighter trainer).

« We’ve known about it for a long time, and due to the extra weight and displaced centre of gravity of JHMCs and NVGs, it continues. »

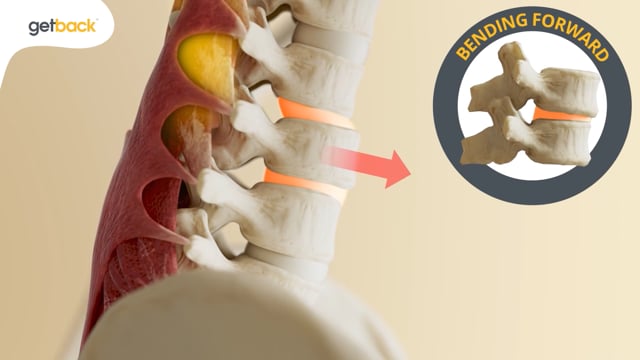

The JHMCS, or the Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System, is a miniature projector system mounted on the forehead of the RAAF Hornet, Super Hornet and Growler aircrews’ Gentex HGU-55B helmet. JHMCS (pronounced ja-him-cus’) entered service with the RAAF in 2007, and projects flight and sensor data onto the inside of the helmet’s visor, which adds additional weight on the front of the helmet.

It places considerable additional strain on a pilot’s neck and upper back.

At 1G the additional forward weight of JHMCS can cause fatigue, when manoeuvring at 7G plus for prolonged periods it places considerable additional strain on a pilot’s neck and upper back, particularly in lateral flight regimes. And the additional weight of night vision goggles (NVG) exacerbates the problem further.

However, aircrew neck problems were prevalent well before the current generation of helmets entered service.

« It’s been a problem as long as we’ve had high-G aircraft, and it’s just been one of those problems that’s been accepted culturally as a part of flying fast jets, » said James Wallace, a human performance specialist and head physiotherapist for Fighter Fit with the RAAF’s Institute of Aviation Medicine (IAM).

« A pilot sits in a cockpit sustaining 5 or 6G for a lot of the time when they’re doing BFM. This peaks out at 7.5G in the Hornet. That means your head and helmet is going to weigh maybe 70 or 80 kilos while you’re moving and twisting it around and trying to keep your eyes on all the other aircraft. It’s very demanding.

« And it’s not just the neck, because you’re also using your torso as well while you’re strapped into the ejection seat, » Wallace continued.

« Physios will tell you the body is not designed to hold that much weight on your head. It has been a problem and air forces around the world have been investigating what to do about it. » Even without performing BFM, long-endurance missions can cause problems.

« The Operation Okra missions were long, often 10-plus hour missions with NVGs, and that illuminated the incidence of fatigue for longer missions as well, » officer commanding 78WG Group Captain Chris Hake said of the recent RAAF Hornet and Super Hornet operational missions over Iraq and Syria.

Even for aircrew who don’t experience ongoing neck and back issues, all require some rehabilitation and a few weeks out of the cockpit every year.

« It’s like any physical profession, » said WGCDR Almenara. « Using professional sport as an example, there is risk of injury and you expect there are times in the season when you’re going to be down. Culturally aircrew accept neck and back pain. Aircrew tend to live with it. »

Finding a feasible economic solution

But rather than just accepting the problems, Air Combat Group decided to start recording injuries and to investigate the cultural aspects of aircrew not reporting problems. This saw ACG in conjunction with the Institute of Aviation Medicine conduct a series of aircrew surveys in 2016, which led to the startling discovery that the RAAF was losing the equivalent of seven man-years of productivity each year across its fast-jet force, primarily due to neck problems. That’s a significant number for a small air force.

The RAAF was losing the equivalent of 7 man-years of productivity each year…primarily due to neck problems.

« On top of that, the majority of us occasionally have some problems that, while we might still be flying, we’re performing at sub-optimal levels, » said WGCDR Almenara.

« Then there is a small percentage of people who get injured to the point that they may never be able to fly a fast jet again due to neck problems. ACG and Air Force decided this was an unacceptable level of attrition. »

While ACG was aware of the problem and had introduced mitigation strategies based on education, self-management and guidance which included limiting the number of sorties a pilot could fly in a week, more needed to be done.

« In my view, the problem with those strategies in the past was that they relied a lot on the individual, » WGCDR Almenara said.

« It was a case of, ‘here are some tools to use and now go and manage yourself and advise us if you have further problems’. But culturally, aircrew just do not come forward when there’s a problem. We just push through it and keep going. »

GPCAPT Hake observed that the problem was more than about just economics.

‘We don’t have to hurt people, and there is a moral dimension to this that we’re very aware of, » he said. « It’s more than the pure economics, however economics is a good driver to get investment. So, ACG has finally seen this as an investment in our people, not a cost, and that’s a big move forward. »

This is as an investment in our people, not a cost, and that’s a big move forward.

ACG established a muscular-skeletal injury steering group.

‘We looked at the whole range of mitigation options, » WGCDR Almenara said. « Initially, we started looking at engineering solutions such as what can we do to modify the cockpit, the helmets, life support equipment and lumbar supports for different postures.

« Some of those were extremely expensive options, including trying to find lighter weight JHMCS and helmets or modify the cockpit environment. But to be honest, it’s questionable how much value we would end up without of that process.

« A new helmet might be a little bit lighter and have a better centre of gravity, but it wasn’t fixing the core of the problem. We’ve been hurting fighter pilot necks since WW2, so whilst it was important if we’ve made the problem worse through design, it probably doesn’t target the root of the issue and provide the best bang-for-buck. »

Creating a successful conditioning program

So, the steering group decided to focus most of its attention on aircrew strength and conditioning, where conditioning, intervention and injury management strategies could be applied from when aircrew first entered the fast-jet world.

« We have a highly motivated workforce that works long hours and is very focused on their tactical excellence, » WGCDR Almenara said.

« Trying to squeeze anything new into their working week is a challenge, so we needed a program that was attractive to them and they could see they were going to get very quick benefits from, but that was also going to be convenient enough to be worked into the battle rhythm without having to impact the operational side of their flying. »

The program needed to be credible and convenient to the squadrons, be flexible enough to their workflow, and be tailorable to an individual’s needs. To that end, the working relationship between the Fighter Fit managers and squadron executives was vital, and similar to the professional sports model where clinical staff liaise with coaches, a model of risk management was put in place.

« Around that time, I contacted one of our lead physios on base, » said WGCDR Almenara. « He and some personal training instructors studied other programs and we started to implement conditioning and risk management strategies within 76SQN. »

In late 2015, 76SQN put its trainee aircrew onto a conditioning program utilizing the David Spine Concept in the lead-up to the high-G part of the IFC, and from that it was able to determine the metrics to start measuring aircrew physical conditions and apply risk categories to individuals.

« Depending on the risk category, we started monitoring them during the high-G part of the course and looking for any early signs of injury that we could start to manage before it became a problem, » WGCDR Almenara said.

« That was successful, and since we’ve done that, I haven’t seen a trainee suspended here for any physical-related problems. »

Such has been the success of the program at 76SQN, WGCDR Almenara says the RAAF has rolled it back to the 79SQN Hawk conversion and 2FTS Wings’ courses at RAAF Pearce, and to the Central Flying School (CFS) at RAAF East Sale.

We’re going to be conditioning candidates all the way through the training system, so they learn to understand and manage themselves, and recognise any signs of potential problems.

Helping all fighter pilots through maintenance

Once aircrew get to the high-G part of the IFC, the program switches from a conditioning to a maintenance phase where there is a system of monitoring the aircrew, so they maintain the standards achieved in the conditioning phase.

Williamtown Fighter Fit sports physiotherapist Toby Watson said the system functions through an app on their smartphone.

« The app was developed for us, » he said. « It looks at specifics such as pain and well-being, but it’s not designed to ground aircrew. It’s designed to identify potential problem areas early, so… »

Excited to read more? Next week’s blog will feature the second part to this intriguing story. Follow us on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter for the latest blogs, news, and updates.

This article was originally published in Australian Aviation magazine in September 2018

Français

Français