Recommendations for Physical Therapy intervention COVID-19 for IC patients

In several studies, muscle weakness, pain, cognitive impairment, delirium, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorders are mentioned as direct consequences of the critical illness [ Herridge 2011, Needham 2012]. ICU-acquired muscle weakness is one of the most striking consequences of critical illness, and also one of the most important focal points for physiotherapy. The cause of this muscle weakness can be in the muscle (critical illness polymyopathy) as well as in the nerve (critical illness polyneuropathy).

Because these conditions often occur simultaneously and are difficult to differentiate, the term ‘intensive care unit acquired weakness’ (ICU-AW) is used. The main risk factors are sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), multiple organ failure (MOF), immobilization and hyperglycemia [Groeneveld 2012]. This muscle weakness has adverse consequences for the withdrawal of ventilation as well as short and long-term recovery.

The incidence of ICU-AW reported in the literature varies depending on the population studied, from 60% in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) to 100% in patients with SIRS in combination with MOF. There is increasing evidence that reducing bed rest and inactivity as much as possible by early mobilization in the chair and activation in the ICU, are promising interventions to prevent and reduce the consequences of bed rest, inactivity and critical illness [Bourdin 2010, Burtin 2009, Gerovasili 2009, Schweickert 2009, Needham 2008].

Physiotherapy in the ICU

Physiotherapy is the paramedical discipline that deals with the prevention and treatment of the effects of bed rest and inactivity in critical illness on moving to function and therefore plays an important role in the multidisciplinary treatment process [Grill 2011, Eeuwes 2010].

Therapeutic process

The overall aim of the treatment is to safely start early with the mobilization and activation of the ICU patient in order to reduce the effects of bed rest and inactivity in critical illness on moving to function. As a result of the diagnostic process, specific treatment goals can be set within the ICU.

Treatment goals focused on anatomical properties:

- Reducing edema in the extremities

- Focusing of treatment objectives to specific functions

- Optimizing and maintaining the ROM

- Optimizing and maintaining muscle strength

- Preventing muscle atrophy

- Normalizing and developingmuscle tone

- Optimizing and maintaining muscle endurance

- Optimizing effort tolerance

Treatment objectives focused on activities, by optimizing and maintaining:

- posture (lying down, sitting, standing)

- transfers > Tip! download the eUlift app

- walking

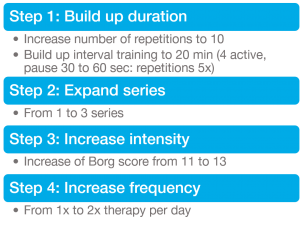

Training buildup:

There is insufficient evidence to formulate a recommendation on the training structure for ICU patients. It is not possible to apply exercise physiology of healthy individuals toseverely ill ICU patients. In addition, training parameters such as heart rate, heart rate reserve and VO2max are not reliable for determining the correct training intensity of an ICU patient.

Experts advise to monitor and evaluate the changes in safety parameters during exercise therapy. Based on this data, exercise therapy can be evaluated and, if necessary, adjusted in terms of treatment frequency, number of repetitions, sets, and duration of the activity. Experts recommend the following training structure for ICU patients:

Conclusion

Globally, the role of care employees has increased in prestige during the COVID-19 crisis. The demand for health will continue to grow in the coming months. People have experienced that their health cannot and should not be taken for granted. Moreover, the role of physical therapists will change considerably.

Is your clinic ready for the future?

Bastiaan Meijer

Digital Marketing Manager

bastiaan.meijer@davidhealth.com

Resources

Bourdin G, Barbier J, Burle J-F, Durante G, Passant S, Vincent B et al. The feasibility of early physical activity in intensive care unit patients: A prospective observational one-center study. Respir.Care 55.4 (2010): 400-07.

Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robbeets C, Ferdinande P, Langer D, Troosters T et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances shortterm functional recovery. Crit Care Med 2009;37(9):2499-2505.

Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Dennison CR et al. Quality of life after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2006;32:1115-1124.

Gerovasili, V., et al. « Electrical muscle stimulation preserves the muscle mass of critically ill patients: a randomized study. » Crit Care 13.5 (2009): R161.

Grill E, Gloor-Juzi T, Huber EO, Stucki G. Assessment of functioning in the acute hospital: operationalisation and reliability testing of ICF categories relevant for physical therapists interventions. J Rehabil Med 2011; 43(2):162-173.

Hermans, G. Intensivecareverworven spierzwakte. In Handboek Multiorgaanfalen, pg 277-286. Groeneveld A.B.J.; Schultz M.J.; Vroom,M.B. De Tijdstroom, Utrecht 2012.

Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1293-1304

Needham D. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: a quility improvement project. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91.

Schweickert WD, Kress JP. Implementing early mobilization interventions in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU. Lancet 2009;373:1874-1882.

Sommers J, Gosselink R, Dettling DS, Spronk PE, van der Schaaf M (2013). Evidence Statement voor fysiotherapie op de Intensive Care, AMC.

van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans DA, Vroom MB, Nollet F. Functional status after intensive care: a challenge for rehabilitation professionals to improve outcome. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:360-366.

Français

Français