Arno’s Journey: From School Metal Class to Starting His Own Company

‘I was very excited about the cam technology they had designed to regulate resistance in training equipment,’ Arno recalls on a recent trip to Melbourne. ‘We went to Florida and had a chance to try these machines.’ He was so excited that when he returned to Finland, he decided to make a copy of the cam in his school metal class. ‘I made a pullover machine and a bicep, tricep, arm machine,’ Arno says. ‘It was in the school gym and it created quite a bit of interest. ‘A medical journal visited us and wrote an article about it, and that’s when I decided “This is something I want to do.”’ A year later he flew back to the United States to meet with the exercise equipment company’s founder.

‘I said that I would love to bring the technology to Scandinavia on a license. ‘He said “We’re too busy… come back in five years and we can talk.’ Though disappointed that he’d been brushed off, Arno put the initiative on hold and set about getting an Economics degree. Exactly five years later, he wrote a letter to the company founder. ‘I still have a copy of that letter,’ Arno recalls. ‘I explained my plan to him in detail. ‘But I never got an answer.’ At this point, most people would have shelved the project for good. But Arno wasn’t about to take no – or radio silence – for an answer. ‘I thought “Okay, I’m able to do this for myself,”’ Arno recalls. ‘So I started a company.’

Arno’s Breakthrough with Exercises Equipment and the Challenges that came with it

With a small grant from the Finnish government, Arno began making prototypes of a pullover machine with a similar cam design. But while testing the device, he discovered a fundamental limitation with its biomechanical properties.

‘We noticed that when you got tired, the range of motion got shorter. I wondered, “Why is that?”’ ‘Then we shaved part of the cam off and put it back together, maybe 20 times. ‘The result was that we could actually squeeze the full range of motion with a steady speed.’ Arno was puzzled that the training effect of his re-fashioned prototype was the opposite of the established cam design. ‘I was very confused,’ he says. ‘This was a multimillion-dollar US company, and we were nobodies, yet our results were totally different.’

Eager to verify his findings, Arno consulted with Professor Paavo Komi, head of the Department of Biology and Physical Activity at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Professor Komi suggested a study using Electromyography (EMG) to analyze how activities spread through the range of motion on Arno’s devices. ‘Although the loading curve dropped dramatically towards the end of the extension on our device, EMG activity stayed the same,’ Arno says.

The study papers published in the mid-1980s gave Arno a solid scientific foundation that they had found something unique about regulating loading in devices. But there were barriers in finding the right application for the new design. ‘We were working with the sports and fitness industry, and our clients were predominantly ex-bodybuilders who started fitness clubs,’ Arno says. ‘When I tried to explain the beauty of the loading curves, it often fell on deaf ears. It’s odd that even today, fitness equipment in the marketplace is not correctly designed.’

The Beginning of David

Despite the barriers, Arno’s new company – David Health – had some success distributing the new devices in Europe and the United States. ’In the late ’80s David was quite a well known brand in the US,’ Arno recalls. ‘We had these beautiful white devices with a big David logo that were quite iconic, and they attracted women. ‘We were even featured in beauty magazines in France!’ But he still felt there was a gap in clients understanding the full capabilities of the devices. ‘I was disillusioned for a time,’ he says. ‘Until Professor Komi suggested we look to adapt the technology for rehabilitation.’ It was the killer application that Arno had been searching for.

‘What was unique about the idea was that nobody was really using strength training or exercise in that format for rehabilitation,’ Arno explains. ‘The only devices that were really accepted were isokinetic devices, where you start pushing the movement arm, and it escapes at a steady speed. ‘But the idea of using a load, or a weight in rehabilitation was quite unique. ‘You’re actually pushing against load that you have to lower down with your force. ‘The difference was that the variable resistance in our devices worked so beautifully. ‘It felt very smooth and easy to handle for patients. They really loved it.’

From David Back Clinic to Global Innovation in Exercise Therapy

The devices were quickly adopted in the rehabilitation environment, particularly for back conditions. Arno developed the David Back Clinic franchise, which peaked at around 200 clinics in 20 countries. Despite his success, Arno didn’t rest on his laurels. The business entered a turbo-charged phase of development when his children Lauri and Elina joined.

‘At the time, we were working with both the medical field and fitness industry, which lacked a clear direction,’ Arno recalls. ‘We decided to scrap about 100 different fitness product models to focus on six back rehabilitation devices.’ This strategic move marked a challenging but deliberate shift towards the medical field.

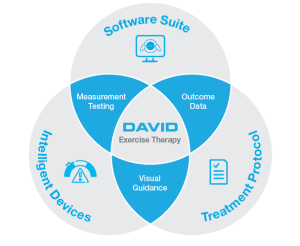

‘You’re fighting not just against competition, but against the establishment,’ Arno states. ‘All the systems, lobbies, and financial insurance schemes posed significant challenges.’ The company also ventured into developing a new generation of ‘intelligent devices.’ ‘Originally, the devices were basic, lacking computers or connections. You could only test isometrically with a cassette,’ Arno explains.

A significant effort was made to connect the devices to the cloud and develop accompanying software. This software automatically collects data from the back rehabilitation devices during every therapy session. ‘Combining structured data with these devices allows for very precise prescription methods,’ Arno notes. The devices’ graphical interface clearly displays prescribed speeds, ranges of motion, workloads, and patient compliance levels, enhancing motivation and empowerment.

Today, David Health devices are utilized in over 600 centers across 45 countries, including 22 clinics in Australia overseen by getback. These changes in the healthcare guidelines reaffirm Arno’s belief in the critical role of exercise therapy within mainstream medical systems.

“There is still work to do”

Recent healthcare guidelines recommending exercise therapy for musculoskeletal disorders have reassured Arno that prioritizing a medical approach was correct. ‘Exercise therapy is now becoming part of mainstream medical systems,’ he says. ‘My long term belief is that that exercise therapy in a scientific, documented and quantified manner will be a huge, core part of healthcare.’

But there is still work to do, and the quest continues for Arno. ‘I’m 68 with no plans to retire at this point, because I have so much energy and so much work to do.’ Perhaps ironically, he is now looking back to the fitness industry, where he sees the potential to merge with medical services to offer mass preventative health, particularly for ageing populations – what Arno calls ‘Population Health’. ‘It’s become very clear to me that we have to bring the medical and fitness sides together now,’ he says. ‘Right now, they’re very far from each other. They don’t talk to each other, and they don’t trust each other. ‘It’s going to reverse, but it will take time. We’re never going to give up.’

Part II of the interview with Arno Parviainen – where he outlines his vision for ‘Population Health’ – will be published soon.

Bastiaan Meijer

Malaysia

Malaysia