1. The Limitations of Traditional Approaches

Traditional back-care programs often focus narrowly on symptom relief through passive treatments, medication, or short-term exercise without progressive loading. However, research shows that long-term improvement is only possible when patients engage in active, structured, and guided rehabilitation that addresses not only physical function but also motivation, beliefs, and behaviour (Foster et al., 2018; O’Sullivan et al., 2019).

2. The DAVID Spine Solution: From Isolation to Integration

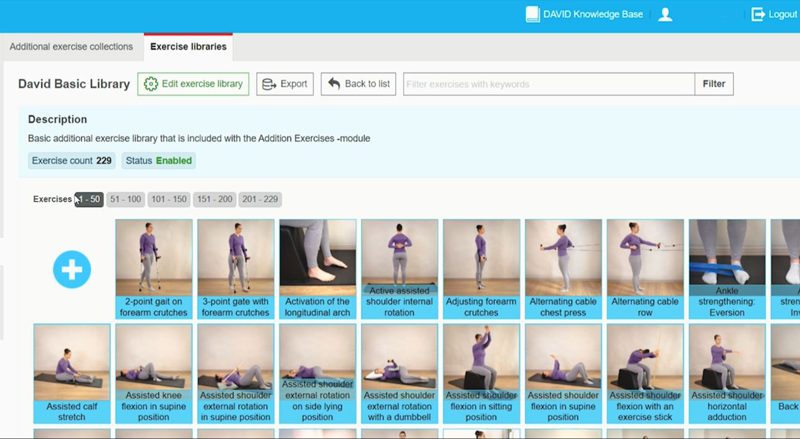

The DAVID Spine Solution comprises intelligent exercise devices that isolate and train all primary directions of spinal movement, including extension, flexion, lateral flexion, and rotation, while restoring neuromuscular control and balance of strength. Through the EVE software, every session, pain score, and questionnaire response is recorded, producing objective, long-term outcome data for both therapist and patient.

Clinical studies have consistently shown that such controlled, progressive, and personalised spine programs lead to substantial improvements in strength, function, and pain perception among chronic back pain patients:

- Taimela et al. (1996) demonstrated that targeted, feedback-guided back extension exercise significantly reduces pain and disability.

- Fehrmann et al. (2017) confirmed the high reliability of DAVID equipment for assessing functional muscle strength.

- A recent Dutch retrospective study (n = 447) reported statistically significant improvements in pain (VAS), disability (ODI/NDI), and kinesiophobia (TSK) after participation in the DAVID Spine program (David Health Solutions, 2025).

3. The Biopsychosocial Model in Practice

The strength of the DAVID approach lies not only in biomechanics but also in the way it integrates biological, psychological, and social dimensions of recovery:

| Dimension | DAVID Approach | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Biological | Controlled and measurable strengthening of deep spinal stabilisers | Improved stability, balance, and movement control |

| Psychological | Visual feedback, data-driven progress, and transparent reporting | Increased confidence and reduced fear of movement |

| Social / Behavioural | Coaching, education, and consistent feedback loops | Higher adherence and long-term lifestyle change |

By involving patients in their own recovery through data visualisation, personalised goals, and measurable outcomes, the therapist’s role evolves from “treatment provider” to coach and partner in health.

4. Objective Data as a Driver of Motivation

The EVE platform provides clear visualisations of training volume, strength progression, and pain scores. This transparency is a key factor in building self-efficacy, a well-established predictor of successful recovery (Bandura, 1997; Louw et al., 2016). When patients can literally see their progress, their confidence grows, and their fear of movement declines.

5. Long-Term Outcomes Through Consistency

A significant advantage of the DAVID Spine program is the ability to follow standardised yet individualised care pathways over time. Longitudinal data indicate that patients not only improve during the program but also maintain their function and quality of life in the long term, provided they continue to move within their learned capacity (Taimela & Hurme, 2000; Choi et al., 2021).

Conclusion

Treating chronic low back pain requires more than strengthening muscles. It requires insight, structure, motivation, and trust — the four pillars united within the DAVID Spine Solution and its biopsychosocial foundation. By combining technology, science, and personalised coaching, DAVID helps healthcare providers around the world shift from passive pain management to active rehabilitation, leading to measurable results and lasting improvement in patients’ quality of life.

References

- Taimela, S., Hurme, M., et al. (1996). Active rehabilitation reduces pain and disability in chronic low back pain patients. Spine, 21(3), 287–294.

- Fehrmann, E., et al. (2017). Reliability of functional muscle strength measurements in low back pain rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med, 49(6), 467–473.

- Foster, N.E., et al. (2018). Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. The Lancet, 391(10137), 2368–2383.

- O’Sullivan, P., Caneiro, J.P., et al. (2019). Cognitive Functional Therapy: An integrated behavioral approach for chronic pain. Phys Ther, 99(9), 1241–1252.

- Louw, A., et al. (2016). The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. Phys Ther, 96(6), 831–845.

- David Health Solutions (2024). Retrospective analysis of 447 chronic back and neck pain patients in the Netherlands. Internal data report.

- Choi, B.K., Verbeek, J.H., et al. (2021). Participatory ergonomics for preventing low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2021(1), CD008565.

English

English