Treatment program and prognosis for neck pain

Neck pain constitutes (J.D. Bier et al., 2016) the fourth most significant category of complaints and symptoms relating to the musculoskeletal system. Most people (approximately 70%) suffer from some form of neck pain during their lives, although it will generally cause little or no interference with their daily activities. Roughly 20% of the European population suffering from neck pain visit a doctor or physical therapist at some point in time. In the general population, 50–85% of patients with neck pain report recurrent or persistent neck pain in the subsequent 5 years.

Neck pain usually decreases by 45%, accompanied by a decrease in the limitations in activities and participation, within 6 weeks of onset pain. This reflects a normal course of recovery. However, if the pain and the limitations in activities and/or participation do not improve or become worse in the first 6 weeks, the course of recovery is considered deviant. Neck pain may fluctuate in severity. Recurrent pain and limitations in activities and/or participation in the first 6 weeks after the first symptoms are considered the same episode of neck pain. The term ‘recurrent pain’ is used when pain recurs after 6 weeks, either once or on multiple occasions. In this case, there may be other functional or anatomical disorders that affect the extent to which activities and/or participation are limited.

Recovery is considered to be ‘normal’ if the neck pain decreases within the first 6 weeks of its onset and/or if activities and/or participation increase. Recovery is considered to be ‘deviant’ if the neck pain persists for longer than 6 weeks or if it recurs

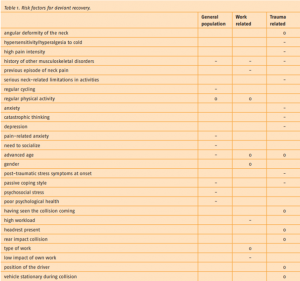

A distinction is also made between trauma-related neck pain and work-related neck pain. Trauma-related neck pain occurs as a result of a trauma. This term is preferred over whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) because of the negative connotations of the term ‘whiplash’. Neck pain that patients think is the result of their work is regarded as work-related neck pain. This classification into subgroups aids the identification of potential risk factors for a deviant recovery (Table 1).

Figure 1: The neck pain guideline (J.D. Bier et al., 2016) of the Dutch Society of Physiotherapy

Figure 1: The neck pain guideline (J.D. Bier et al., 2016) of the Dutch Society of Physiotherapy

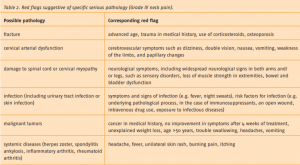

Neck pain red flags

During the first consultation, it is essential that the physical therapist exclude serious pathology (Grade IV neck pain), based on the pattern of symptoms and red flags. Once Grade IV neck pain has been excluded, the physical therapist should distinguish between Grade I, II, and III neck pain and treat accordingly.

Figure 2: The neck pain guideline (J.D. Bier et al., 2016) of the Dutch Society of Physiotherapy

Figure 2: The neck pain guideline (J.D. Bier et al., 2016) of the Dutch Society of Physiotherapy

Evaluation and diagnosis of neck pain

The physical therapist (J.D. Bier et al., 2016) should use the information from the case history and the findings of the physical examination to evaluate the neck pain, other potential functional or anatomical disorders, activity limitations and/or participation restrictions, and any interaction between them. This will enable the therapist to chart the patient’s health problem and provide an answer to the following questions:

1. How severe (grade) is the neck pain?

2. Do complaints or symptoms follow a normal or deviant course of recovery?

3. Does the patient have trauma-related or work-related neck pain?

4. Are there risk factors (psychosocial, personal, and environmental factors) for a deviant course of recovery, and can these factors be influenced by physical therapy?

5. Is there a link between the activity limitations and/or participation restrictions and neck pain or other functional/anatomical disorders, and can this link be influenced by physical therapy?

Neck pain patient case

How does neck pain treatment work in practice? Let us take a look at a patient case and see how the initial consultation and treatment plan occur. After the treatment program, we can take a look at the treatment outcomes and how they are evaluated.

Age: 66 old female

Height: 168 cm

Weight 85.6 KG

BMI: 30.3

Country: Netherlands

How severe (grade) is neck pain? Grade I/II neck pain

Do complaints or symptoms follow a normal or deviant course of recovery? Yes, deviant course of recovery: neck pain that (to a greater or lesser extent) interferes with daily activities and which is expected to have a deviant course of recovery. The dominant presence of psychosocial factors that delay or inhibit recovery.

Does the patient have trauma-related or work-related neck pain? trauma-related

Are there risk factors (psychosocial, personal, and environmental factors) for a deviant course of recovery, and can these factors be influenced by physical therapy? Yes, psychosocial and environmental factors.

Is there a link between the activity limitations and/or participation restrictions and neck pain or other functional/anatomical disorders, and can this link be influenced by physical therapy? No

Screening red flags: No red flags

Once an indication for physical therapy has been established, the physical therapist creates a tailored treatment plan in consultation with the patient. A third party (e.g. from another discipline, such as a psychologist or a company doctor) may also be involved.

Treatment Plan

Grade I/II neck pain with a deviant course of recovery: neck pain that (to a greater or lesser extent) interferes with daily activities and which is expected to have a deviant course of recovery. The dominant presence of psychosocial factors that delay or inhibit recovery.

Treatment should focus on the factors (both physical and non-physical) that delay or inhibit recovery, with a particular focus on psychosocial factors. It is less effective to focus on pain because this will only increase the patient’s awareness of pain and resulting pain behavior.

- Combine exercise therapy with cervical and/or thoracic mobilization or manipulation*

- Tailor exercise therapy to the patient’s needs, limitations, and goals.

Information and advice

- Emphasize that psychosocial factors (anxiety, restlessness, depression, fear of movement (kinesiophobia), catastrophic thinking, and so on) may adversely affect recovery.

- Regarding fear of movement (kinesiophobia) or pain-related anxiety, explain that an increase in activity will facilitate recovery and encourage the patient to take more exercise.

- Regularly discuss the impact of psychosocial factors that could delay recovery, to check whether these factors have changed and whether their impact on neck pain has decreased.

- If psychosocial factors indeed hinder recovery, the patient should be encouraged to contact his/her GP, psychologist, and/or psychosomatic physical therapist and discuss treatment options.

- In exercise therapy, place more emphasis on behavioral principles and encourage a gradual increase in physical activity.

Exercise therapy program (based on clinic best-practice)

- 12 week training 2x times a week

- Include DAVID G110, G120, G130, G140 G150, G160

- Phase 1: 4 weeks 8 visits > 25% of max strength

- Phase 2: 2 weeks 4 visits > 30% of max strength

- Phase 3: 3 weeks 6 visits > 35% of max strength

- Phase 4: 3 weeks 6 visits > 40% of max strength

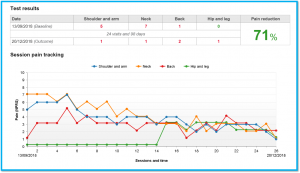

Treatment Evaluation

Pain Score (NPRS)

Neck pain significantly decreased from a pain score of 7 at the start of treatment to a pain score of 1 at the end of 12 weeks of the program.

| Pain score (NPRS) | T0 | T1 after 12 weeks |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder and arm | 5 | 1 |

| Neck | 7 | 1 |

| Back | 1 | 2 |

| Hip and Leg | 0 | 1 |

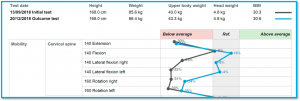

Mobility

Mobility of the cervical spine increased. Cervical extension increased by 1.7%, cervical flexion by 14.8%, cervical lateral flexion right by 44.5%, cervical lateral flexion left by 64.3%, Cervical rotation right by 21.9 and Cervical rotation left by 21.2%.

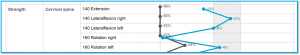

Strength

The strength of the cervical spine increased. Cervical extension increased by 97%,, cervical lateral flexion right by 156%, cervical lateral flexion left by 93.3%, Cervical rotation right by 253.8% and Cervical rotation left by 25.5%.

Conclusion

Quantifying exercise therapy helps to provide insight into the course of treatment for both the therapist and the patient. The exercise equipment allows the therapist to limit the patient’s range of motion and weight resistance. When the patient is both mentally and physically ready, the therapist can increase these exercise parameters. Quantified results allow for a better understanding of the treatment outcomes. In this specific example, the patient’s perceived pain has decreased, and strength and mobility have improved significantly.

References

[1] Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (2018) J.D. Bier, G.G.M. Scholten-PeetersII, J.B. StaalIII, J. Poo, M. van Tulder, E. Beekman, G.M. Meerhoff, J. Knoop, A.P. Verhagen: Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy, Neck Pain Guideline.

English

English